Japanese washi paper represents one of the most remarkable achievements in traditional craftsmanship. Made from long plant fibers—primarily kozo (paper mulberry), gampi, and mitsumata—along with secondary materials like hemp and bamboo, washi has earned worldwide respect for qualities that ordinary paper simply cannot match.

What makes washi special comes down to three things: exceptional strength despite its light weight, a beautiful unique texture that feels alive under your fingers, and longevity that surpasses most paper made from Western wood-pulp methods. These qualities explain why washi has been used for centuries in everything from imperial documents to temple scrolls, and why conservators today still rely on it to restore fragile artworks.

This article covers what washi is, how it’s made using traditional techniques refined over 1,400 years, its history across Japan, the key types available today, and practical tips for choosing the right paper for your art, craft, or conservation work. Whether you’re exploring Japanese washi paper for the first time or deepening existing knowledge, you’ll find the essentials here.

- What Is Washi? Materials and Basic Features

- History of Washi and Japanese Papermaking

- Raw Materials of Washi Paper

- How Handmade Washi Is Made (Shoshi 抄紙)

- Basic Characteristics and Preservation Qualities of Washi

- Types of Washi: From Everyday Sheets to Specialty Papers

- How to Choose Washi Paper for Your Project

What Is Washi? Materials and Basic Features

Washi is handmade (or hand-finished) paper crafted from the inner bark of specific plants—kozo, mitsumata, and gampi—rather than the wood pulp used in mass-produced printer paper and books. This fundamental difference in raw materials creates paper with dramatically different properties. Where wood-pulp papers rely on short, chemically processed fibers, washi depends on long fibers extracted through careful, traditionally refined processes.

The core physical characteristics of washi are immediately noticeable: sheets are light yet remarkably strong, with a slightly warm white tone that reflects the natural materials rather than chemical bleaching. You’ll often see visible fibers running through the sheet, giving each piece its own character. The structure feels supple but resists tearing in ways that surprise people accustomed to ordinary paper.

Traditional Japanese paper serves an extraordinary range of purposes. Artists use it for sumi e ink painting, where the fiber structure allows beautiful gradations of black ink. Calligraphy practitioners (practicing shodō) prize washi for how it accepts brush strokes. Historic applications include ukiyo-e woodblock prints from the Edo period (17th–19th centuries), where the paper’s strength allowed hundreds of impressions from carved blocks. Beyond art, washi forms the translucent panels in shoji screens and sliding doors, creates durable lanterns, and serves conservators who need archival-quality material for mounting and repairs, offering a distinct alternative to common craft paper supplies used in DIY projects..

High-quality washi is typically neutral to slightly alkaline in pH and free from the lignin that causes wood-pulp paper to yellow and crumble. This acid free quality makes it suitable for archival uses—backing 18th–19th century scrolls, repairing early modern books, or creating long lasting paper supports that will remain stable for centuries.

History of Washi and Japanese Papermaking

The roots of making paper trace back to China in the 2nd century BCE, where craftspeople first discovered how to transform plant fibers into thin, writable sheets. This technology spread gradually across Asia, reaching Japan around 610 CE during the Asuka period. Korean Buddhist monks brought papermaking knowledge to Japan, where local artisans quickly adapted the techniques to native plants—particularly kozo, which grew abundantly throughout the islands.

By the Nara and Heian periods (8th–12th centuries), washi making had become essential to Japanese culture. Imperial documents were written on carefully prepared sheets, Buddhist sutras were copied onto papers designed to last centuries, and aristocratic poetry manuscripts—including those from the era of “The Tale of Genji”—showcased increasingly refined papermaking. The beauty and durability of Japanese paper became inseparable from the culture’s literary and religious life.

Regional papermaking centers emerged across Japan, each developing distinctive styles shaped by local water quality, climate, and plant varieties. Mino in Gifu Prefecture became famous for thin, strong papers. Tosa in Kochi Prefecture specialized in exceptionally delicate sheets. Echizen in Fukui Prefecture produced papers prized for calligraphy and printing. Cold weather during winter proved ideal for papermaking, as clean mountain streams and low temperatures helped produce exceptionally pure, strong fibers.

Recognition of washi’s cultural significance reached an international milestone in 2014, when UNESCO inscribed “Washi, craftsmanship of traditional Japanese handmade paper” as an Intangible Cultural Heritage. The designation specifically honored papers from regions like Mino, Misumi-cho (Shimane Prefecture), and Ogawa/Higashi-chichibu (Saitama Prefecture), where families have maintained centuries-old traditions.

Industrialization in the late 19th and 20th centuries brought mass-produced Western-style paper to Japan, displacing washi from everyday use. Yet small workshops and family studios preserved traditional methods, recognizing that machine-made paper could never replicate washi’s qualities for art, restoration, and craft. Today, these artisans continue a living tradition that connects modern users to over a millennium of Japanese papermaking history.

Raw Materials of Washi Paper

The strength and beauty of washi depend entirely on its raw materials. Unlike wood-pulp papers made from short, chemically processed tree fibers, washi uses bast fibers—the tough inner bark of specific shrubs and trees. These fibers measure several millimeters or more in length, dramatically longer than wood-pulp fibers, which accounts for washi’s remarkable toughness when compared with typical handmade paper sheets crafted from recycled pulp..

Three plants dominate traditional washi production: kozo, mitsumata, and gampi. Each produces paper with distinct characteristics suited to different applications. Secondary materials include hemp, bamboo, and various blended pulps used in modern or experimental washi, expanding the range of textures and properties available to artists and craftspeople.

The long bast fibers interlock during sheet formation, creating bonds that give thin sheets remarkable tear resistance—even when wet. This combination of delicate appearance and hidden strength defines washi’s practical value across centuries of use. Understanding each fiber source helps you choose papers suited to your specific needs.

Kozo (Paper Mulberry)

Kozo, derived from the paper mulberry tree (Broussonetia species), is the most commonly used fiber for traditional washi. Cultivated across Japan in regions like Kochi, Gifu, and Saitama, kozo thrives in the country’s temperate climate and has been the backbone of Japanese papermaking since the craft arrived from China.

The cultivation cycle requires patience. After planting, kozo shoots grow for two to three years until the bark becomes thick enough for harvesting. Harvesting typically occurs in late autumn to early winter—November through January—after the leaves fall and the plant’s energy concentrates in the bark. This timing, combined with cold weather conditions, contributes to fiber quality.

Harvested shoots undergo steaming to loosen the bark, which is then stripped away and separated into outer (kurokawa) and inner (shirokawa) layers. The inner bark becomes the primary raw material for many washi types. Workers meticulously remove any remaining impurities, ensuring only the cleanest fibers reach the papermaking vat.

Kozo paper properties include notable strength, a slightly crisp hand, and usually an off-white to natural cream color. The paper handles well when wet—a crucial quality for traditional techniques like mounting scrolls. Common uses span shoji screens and fusuma sliding doors in traditional Japanese architecture, fine art printing and painting, calligraphy practice, and ultra-thin conservation tissues like tengujo used worldwide in museum restoration; kozo papers also fold cleanly for intricate origami designs suitable for every skill level..

Mitsumata

Mitsumata (Edgeworthia chrysantha) grows as a shrub on mountain slopes, often cultivated among cedar and cypress plantations in regions like Tochigi and Kochi. The plant’s distinctive three-branched structure gives it its name (“mitsu” meaning three, “mata” meaning fork).

Harvesting occurs in late winter to early spring, when the plant is dormant but before new growth begins. Cut branches are often stored in running water—river or stream—to maintain moisture before processing. Mitsumata fibers require gentler treatment than kozo throughout the preparation process.

The resulting mitsumata fibers yield a naturally soft, slightly glossy paper with a warm tone and smooth surface. The paper absorbs ink beautifully and resists insect damage better than many alternatives. Starting in the late 19th century, Japanese authorities recognized these qualities and adopted high-quality mitsumata paper for banknotes—a use that continues today. The fiber’s combination of strength, durability, and resistance to forgery made it ideal for currency, while artists appreciate the same qualities for high-end writing paper and printmaking surfaces.

Gampi

Gampi (Diplomorpha or Wikstroemia species) stands apart from kozo and mitsumata in several ways. Rather than being widely cultivated, gampi is usually gathered from wild plants, making it rarer and more expensive. Harvesting occurs in spring when stems are full of moisture and sap.

Processing gampi presents unique challenges. Unlike the other fibers, gampi is difficult to steam and requires specialized handling, which limits large-scale production. This difficulty contributes to gampi’s status as a premium material reserved for specialty papers rather than everyday production.

Gampi paper rewards these extra efforts with exceptional qualities: a natural sheen, smooth surface, and high resistance to both insects and damp conditions. The sheets have a crisp, refined character that has made them prized for fine calligraphy, printing, and backing gold leaf since at least the Heian period. Historically, gampi papers appeared in high-end documents, backed paintings, and luxury prints. Today, conservators and luxury stationery makers continue to seek out gampi for applications where only the finest materials will do.

How Handmade Washi Is Made (Shoshi 抄紙)

The transformation from plant bark to finished paper involves multiple stages refined over centuries of practice. The basic workflow includes preparing raw fibers, cooking and cleaning them, beating the fibers into pulp, adding neri (a natural formation aid), and finally sheet-forming, pressing, and drying.

While processes vary by region and paper type, core techniques remain consistent across major papermaking centers like Mino, Tosa, and Echizen. Each step requires skill and attention—rushing or cutting corners shows immediately in the finished paper’s quality. The methods described below represent the traditional approach that produces authentic washi, though modern workshops may incorporate some mechanized equipment while maintaining essential techniques.

Two main sheet-forming methods dominate Japanese papermaking: nagashi-zuki and tame zuki. Both will be explained in detail below, as the choice of method significantly affects final paper characteristics.

Preparation of Raw Materials

Preparing raw bark for papermaking demands time and care. The sequence begins with steaming bundles of kozo or mitsumata to loosen the bark from the woody core. Workers then strip the bark away, carefully removing the outer dark bark layer and preserving the valuable inner bark. These inner bark sheets are dried in the sun for storage, awaiting the next processing stages.

When ready for papermaking, dried inner bark is soaked in clean water—typically for about 24 hours—to rehydrate the fibers. The softened bark then goes into a large vat for boiling (shajuku) in an alkaline solution traditionally made from wood ash, though modern producers may use chemicals like soda ash or caustic soda. This cooking process removes lignin, pectin, and remaining impurities while softening the fibers for the next stage.

After boiling, fibers receive thorough rinsing in running water—often cold river or stream water during winter months, which helps produce cleaner, stronger fibers. Workers then pick through the fibers by hand in a process called chiritori, removing any remaining blemishes, bark fragments, or discoloration. This painstaking inspection directly affects final paper quality.

The beating stage (koukai) transforms softened fibers into usable pulp. Traditionally, workers pounded fibers with wooden mallets; today, mechanized beaters accomplish the same goal more efficiently. The beating continues until fibers separate into a uniform consistency suitable for sheet formation. Finally, a plant-based formation aid called neri—usually derived from tororo-aoi roots—is mixed into the papermaking vat. This mucilaginous substance slows water drainage and keeps fibers evenly dispersed, enabling the creation of thin, uniform sheets.

Methods of Scooping Pulp: Nagashi-zuki and Tame-zuki

Both traditional methods involve the papermaker standing at a vat (sukibeta) filled with pulp suspended in water and neri. The papermaker holds a su (bamboo screen) within a keta (wooden frame), dipping and moving this mold through the mixture to form each sheet.

Nagashi-zuki (“flowing scooping”) dominates Japanese washi making and produces the papers most associated with the tradition. The papermaker scoops pulp onto the screen, then rocks the mold repeatedly back and forth and side to side. This rocking motion—often supported by a flexible bamboo pole suspended from the ceiling—causes fibers to intertwine in multiple directions, creating exceptionally strong bonds. The technique allows papermakers to build up sheets in layers, controlling thickness with remarkable precision. Nagashi-zuki produces the thin, strong, even sheets characteristic of high-quality washi.

Tame-zuki (“static scooping”) resembles some Western handmade paper methods more closely. The papermaker relies more on gravity and fewer rocking motions, allowing pulp to settle on the screen with less fiber interlocking. This approach typically produces slightly thicker, softer sheets with different characteristics than nagashi-zuki papers.

Each method produces paper suited to different purposes. Artisans choose based on local tradition, intended use, and desired paper characteristics. Restoration tissues requiring maximum strength typically use nagashi-zuki, while certain writing papers might employ tame-zuki for a softer surface.

Basic Characteristics and Preservation Qualities of Washi

Washi combines physical strength, flexibility, and aesthetic warmth in ways that make it equally valuable for everyday objects and long-term preservation. These properties emerge directly from the materials and methods described above—long fibers, careful processing, and traditional forming techniques all contribute to the final product’s exceptional qualities.

Surface and color traits distinguish washi immediately from machine-made alternatives. Sheets are usually smooth but retain subtle texture from the bamboo screen and from visible fibers within the paper. Colors range from warm off-white to natural cream tones, reflecting unbleached plant fibers and minimal chemical processing. Some papers show deliberately included bark specks or colored threads, adding visual interest.

Traditional washi is neutral to mildly alkaline in pH and low in lignin—the compound responsible for yellowing and brittleness in acidic wood-pulp papers from the late 19th and 20th centuries. This stability means properly stored washi can last for centuries without degradation, explaining its continued use for important documents and artworks.

Moisture behavior sets washi apart from many papers. The long fibers absorb and release humidity readily, helping stabilize conditions around mounted artworks or scrolls. This quality reduces stress on pigments and supports, making washi ideal for conservation mounting. Conservators worldwide rely on thin tengujo tissues for mending tears in Western prints, kozo backings for hanging scrolls, and various washi products for restoration projects. Major conservation laboratories in Europe and North America adopted Japanese paper techniques from the late 20th century onward, recognizing that no Western material matched washi’s combination of strength, flexibility, and archival stability.

Types of Washi: From Everyday Sheets to Specialty Papers

The world of Japanese washi paper encompasses hundreds of varieties, each developed for specific purposes over centuries of refinement. Understanding the major categories helps you navigate this diversity and find papers suited to your needs.

This section covers notable washi families: kozo papers for general use and art, yuzen patterned papers for decoration, chiri and unryu textured papers for visual interest, and ultra-thin tengujo tissues for conservation and delicate layering. Each type offers distinct properties shaped by fiber choice, thickness, surface treatment, and production method.

Kozo Papers

When people refer simply to “kozo paper,” they usually mean sheets where kozo is the primary or sole fiber. This broad category spans thin conservation tissues weighing just a few grams per square meter to heavier sheets suitable for painting and shoji screens.

Common traits across kozo papers include thin but firm sheets, strong wet strength (crucial for mounting and printmaking), a slightly crisp hand, and visible long fibers that give each sheet character. These properties make kozo papers the workhorse of traditional washi applications—suitable for mounting (hyoso), woodblock printmaking, calligraphy, and countless crafts.

Traditional Japanese houses use kozo paper for shoji screens and fusuma sliding doors, where the paper must withstand years of use while admitting soft, diffused light. Fine art applications include woodblock prints in the tradition of Edo-period ukiyo-e, where the paper must accept multiple layers of pigment while maintaining crisp detail.

Sizing (dosa) significantly affects how kozo papers behave with ink and paint. Dosa-treated sheets resist ink bleeding, producing sharp lines for calligraphy and detailed painting. Unsized sheets allow expressive ink spread favored in sumi e and other styles where soft gradations matter more than precise edges. Understanding this distinction helps you choose papers matched to your intended technique.

Yuzen Patterned Papers

Yuzen washi represents the decorative pinnacle of Japanese paper, featuring colorful, intricate patterns derived from kimono dyeing techniques developed in Kyoto during the Edo period. These papers transform functional washi into visual art.

Traditional yuzen production involves multiple printing or stenciling stages, adding one color at a time by hand. Some patterns incorporate metallic pigments or gold and silver accents that catch light beautifully. The process requires considerable skill, as each color must align precisely with existing elements.

Typical motifs include seasonal flowers (cherry blossoms, chrysanthemums, plum blossoms), fans, waves, cranes, and other auspicious designs reflecting Japanese aesthetic traditions. These papers serve countless decorative purposes: origami for special occasions, gift wrapping that becomes part of the gift itself, book covers, wall decorations, and interior accents.

The visual impact of yuzen papers comes from bright but refined colors, precise outlines, and sometimes a slight relief where pigments accumulate. Running your fingers across a yuzen sheet, you can feel the texture where the design was applied. This tactile quality adds another dimension to the paper’s beauty.

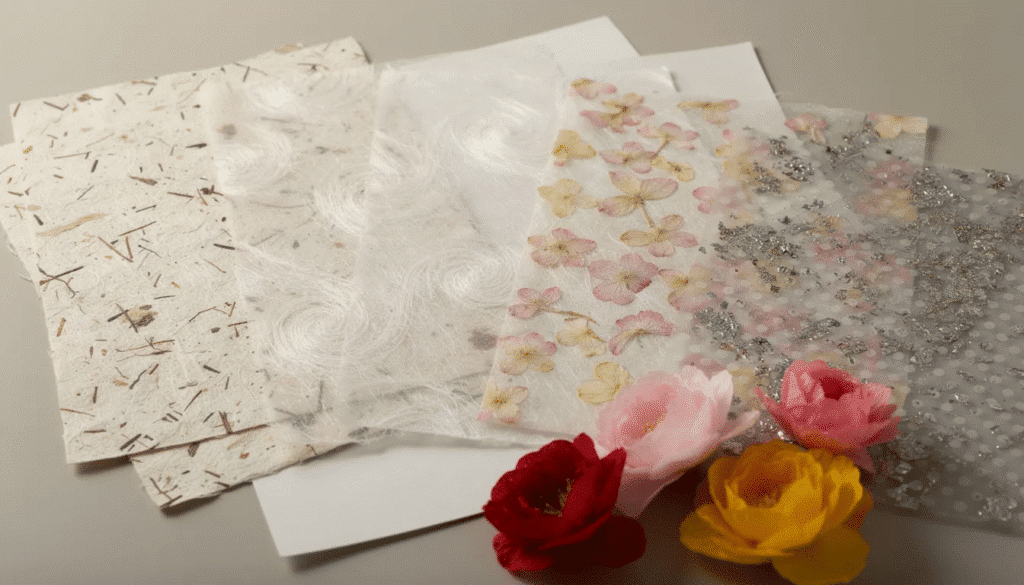

Chiri, Unryu, and Other Textured Papers

Chiri papers incorporate small pieces of unrefined kozo bark scattered across the sheet, creating speckled brown or dark fibers against a lighter background. This deliberate inclusion of “impurities” emphasizes the handmade, natural origin of the paper and adds visual depth without compromising strength.

Unryu papers (the name means “cloud dragon”) contain long, swirling fibers visible throughout the sheet. These fibers create dynamic, cloud-like patterns that make each piece unique. The effect works beautifully in overlays, collage, and lampshades, where light passing through reveals the fiber patterns.

Other decorative variations expand the possibilities further: papers with embedded flower petals, metallic flakes that sparkle in light, or drops that form dot patterns across the surface. These specialty papers add depth to layering, scrapbooking, mixed-media work, and any project where visual and tactile interest matters as much as paper function, and they pair beautifully with colorful tissue paper flowers for any occasion..

Textured papers are commonly chosen as accent layers in design projects, providing contrast against smoother papers or adding natural elements to otherwise uniform compositions. Their beauty lies in combining washi’s traditional strength with contemporary creative possibilities.

Tengujo and Ultra-Thin Conservation Papers

Tengujo represents the extreme end of washi thinness—some modern examples reach approximately 2 g/m², making them among the lightest papers ever produced. Despite this delicate appearance, tengujo retains surprising strength from its long kozo fibers, allowing it to reinforce fragile materials without adding bulk.

Conservation professionals worldwide rely on these papers for restoration work. Applications include reinforcing fragile book pages that have become brittle with age, mending tears in valuable prints without visible repair lines, and backing delicate artworks to stabilize them for display or storage. The papers’ transparency means repairs remain nearly invisible, while their strength ensures lasting support.

Well-known production areas include Tosa (Kochi Prefecture), where papermaking traditions span centuries. Certain tengujo papers have been used in high-profile restoration projects across Europe and America, from Renaissance drawings to 19th-century photographs. The papers’ reputation for quality and consistency makes them the material of choice when irreplaceable artworks need conservation attention.

In creative work, artists use ultra-thin washi for layering effects—placing translucent sheets over paintings or prints to create soft veils of color or texture. The technique recalls traditional urazaishiki methods used in Japanese silk painting, adapted for contemporary mixed-media practice.

How to Choose Washi Paper for Your Project

Selecting the right washi means matching paper properties to your intended technique and aesthetic goals. The variety available can seem overwhelming at first, but focusing on a few key factors simplifies the decision.

Consider these primary decision factors: fiber type (kozo for strength, mitsumata for softness, gampi for sheen, or blends for specific effects), thickness and weight (measured in grams per square meter), level of sizing (dosa for controlled ink behavior vs. unsized for expressive spread), surface smoothness versus texture, and base color tone (natural cream to bright white).

For calligraphy and sumi e, look for papers sized to control ink spread if you want crisp strokes, or unsized papers if you prefer soft, diffused effects. Medium-weight kozo papers work well for practice, while finer mitsumata or gampi papers suit finished work intended for display. The paper should accept your brush strokes without excessive bleeding while allowing subtle gradations.

Watercolor and mixed media require papers that can handle wet applications without falling apart. Heavier kozo papers (50 g/m² or above) generally perform well, though exact requirements depend on how wet your technique becomes. Some artists size their own papers or choose pre-sized options for maximum control. Testing is essential here, as different papers interact with watercolors in surprisingly varied ways.

Printmaking needs vary by technique. Woodblock printing traditionally uses thin, strong kozo papers that accept pigment well and release cleanly from blocks. Etching and intaglio may require heavier papers with more sizing. Silkscreen printing works best on smooth-surfaced papers that allow crisp ink transfer. Understanding your printing method helps narrow choices considerably.

For origami and paper craft, thickness matters most—papers must fold cleanly without cracking or becoming too bulky at multiple-fold points, just as with other types of paper for craft and their uses.. Many crafters prefer papers between 20-40 g/m², though exact preferences vary by project complexity. Yuzen and other patterned papers add visual interest to finished pieces.

Archival and conservation uses demand proven materials. Look for papers from established producers with documented pH levels and fiber content. When matching repairs to existing documents, fiber type and color tone matter as much as thickness. Conservation-grade suppliers typically provide detailed specifications for their papers.

Starting with sample packs or small test sheets saves both money and frustration. Testing how your specific inks, paints, or printing plates behave on different washi surfaces reveals nuances that no description can fully convey. Many suppliers offer sample collections organized by fiber type or intended use, making experimentation accessible even for beginners exploring Japanese paper for the first time, especially those already inspired by general paper crafting tutorials and project ideas..

Whether you’re mounting a delicate scroll, creating original prints, practicing calligraphy, or exploring mixed-media techniques, understanding washi’s materials and properties helps you choose wisely, particularly if you plan to create creative and useful printed projects on paper.. The papers that have served Japanese artists for over a millennium continue offering contemporary creators unmatched combinations of strength, beauty, and durability.