Walk into any office, pick up a book, or grab a coffee cup, and you’re holding a product that started as a living plant. The question “paper is made from which plant?” seems simple, but the answer spans thousands of years of human innovation. From ancient papyrus reeds along the Nile to massive tree plantations in Brazil, the plants we use to make paper have evolved dramatically—and continue to change today. This article is for students, educators, and anyone curious about the origins of everyday materials, helping you understand how the plants used for paper have changed over time and why it matters for sustainability and industry.

Quick answer: which plant is paper made from today?

Most modern paper is made from trees—specifically softwoods like spruce, pine, and fir, along with hardwoods like birch and eucalyptus. There is no single “paper plant.” Instead, paper mills source cellulose fibers from whichever plants best suit their products and supply chains.

- Paper is made primarily from the cellulose found in wood, which provides the structural fibers that form sheets. Cellulose fibers are plant-based fibers that are the main component of paper.

- Beyond trees, manufacturers also use bamboo, cotton, hemp, sugarcane bagasse, and agricultural residues like wheat straw.

- The vast majority of global paper production—over 90%—comes from wood pulp sourced from tree plantations and managed forests.

- Recycled paper products account for a significant share of raw material in many countries, with the remainder coming from non-wood plants.

Historically, people made paper and paper-like materials from very different plants. Ancient Egyptians used the Cyperus papyrus plant, while early Chinese papermakers relied on mulberry bark and hemp. Wood became the dominant source only after the mid-1800s, when industrial papermaking took off.

- From papyrus to paper: early plant sources

- Which plant was used for the first real paper in China?

- Why is modern paper mostly made from trees?

- Non-wood plants used to make paper

- How plants become paper: from fiber to sheet

- Environmental considerations of plant-based paper

- Summary: so, paper is made from which plant?

From papyrus to paper: early plant sources

Before wood pulp dominated the paper industry, people across the world created writing surfaces from various forms of plant material. However, it’s important to distinguish between true paper—made from macerated fiber pulp—and earlier materials that were simply processed plant parts pressed together.

Papyrus in ancient Egypt:

- Papyrus sheets were made from the Cyperus papyrus plant, a tall reed that grew along the Nile River.

- Craftspeople sliced the plant’s pith into thin strips, laid them crosswise in two layers, and pressed them into a laminated thin sheet.

- By around 3000 BCE, papyrus scrolls served as the primary writing surface across Egypt and the Mediterranean world.

- Crucially, papyrus is not true paper—the fibers were never broken down into fine pulp, just layered and pressed.

Other early plant-based writing materials:

- Bark: Birch bark served as writing material in northern Europe and Russia, with letters and documents preserved for centuries.

- Palm leaves: In South and Southeast Asia, dried palm fronds were incised with styluses and covered with ink.

- Bamboo strips and wooden slips: Early China used thin slats of bamboo or wood bound together with cord.

- Barkcloth: Pacific Island cultures and parts of Asia pounded the inner bark of trees like paper mulberry into flexible sheets.

These materials were precursors to paper, but true papermaking required a fundamentally different process: breaking plants down into a fiber slurry that could be formed into a continuous paper web.

Which plant was used for the first real paper in China?

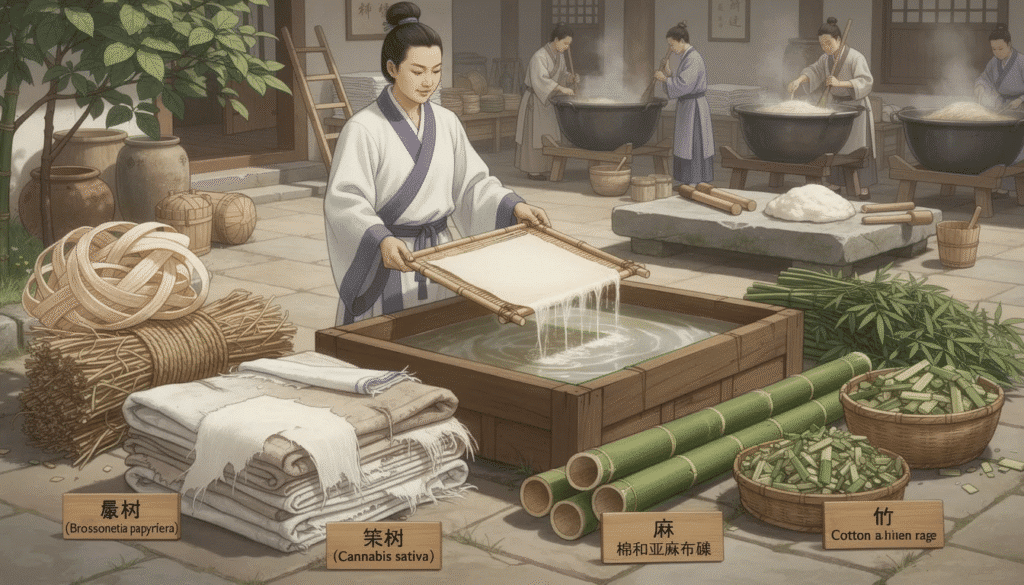

True paper—made by suspending plant fibers in water and forming them into sheets—was invented in China. Archaeological evidence suggests paper production began as early as the 2nd century BCE, though the technique is traditionally credited to Cai Lun, a Han Dynasty court official, around 105 CE.

Key plants used in early Chinese papermaking:

- Paper mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera): The inner bark of this tree provided long, strong fibers that became a main ingredient in early papers.

- Hemp: Waste from hemp ropes and textiles offered durable fibers already separated from the plant.

- Cotton and linen rags: Old clothing and fabric scraps were recycled into pulp.

- Bamboo: In southern regions, bamboo stalks were cooked and beaten into usable fibers.

The basic early process:

- Plant materials were soaked in water for days or weeks to soften them.

- The softened fibers were beaten and pounded until they separated into a fine pulp suspended in water.

- A craftsperson dipped a screen (often a bamboo mould covered with wire mesh or cloth) into the slurry.

- As water drained away, the fibers interlocked on the screen’s surface to form one sheet.

- The wet sheet was pressed to remove excess water, then dried in the sun or over heat.

These non-wood plants provided long, flexible fibers that gave early handmade paper sheets remarkable durability. Some Chinese papers from over a thousand years ago remain readable today—a quality many cheap modern papers cannot match..

Why is modern paper mostly made from trees?

For centuries, paper was made from rags, bark, and agricultural plants. That changed in the 1840s when inventors in Germany and Canada independently developed methods to grind wood into pulp suitable for papermaking. Friedrich Gottlob Keller patented a wood-grinding machine in Germany, while Charles Fenerty in Nova Scotia experimented with spruce pulp. These innovations triggered a shift that transformed the paper industry forever.

Why trees became the dominant raw material:

- Availability: Vast forests in Europe, North America, and other regions provided enormous volumes of pulpwood. Sawmill residues—chips and scraps left over from lumber production—became an additional supply.

- Fiber quality: Softwood trees like spruce, pine, and fir produce long cellulose fibers (2-4mm) that give paper strength and tear resistance. Hardwoods like birch and eucalyptus yield shorter fibers that create smoother printing surfaces.

- Industrial scalability: Wood can be chipped, cooked, and processed continuously in large paper mills operating around the clock.

- Forestry cycles: Commercial trees grown for paper can be harvested on rotations of 10-30 years, depending on species and climate—far faster than old-growth forests but sufficient for sustained production.

Although “which plant” suggests a single answer, modern paper manufacture typically blends fibers from several tree species. Mills adjust their fiber mix to achieve the right balance of strength, brightness, opacity, and cost for each product type.

Main tree species used for paper pulp

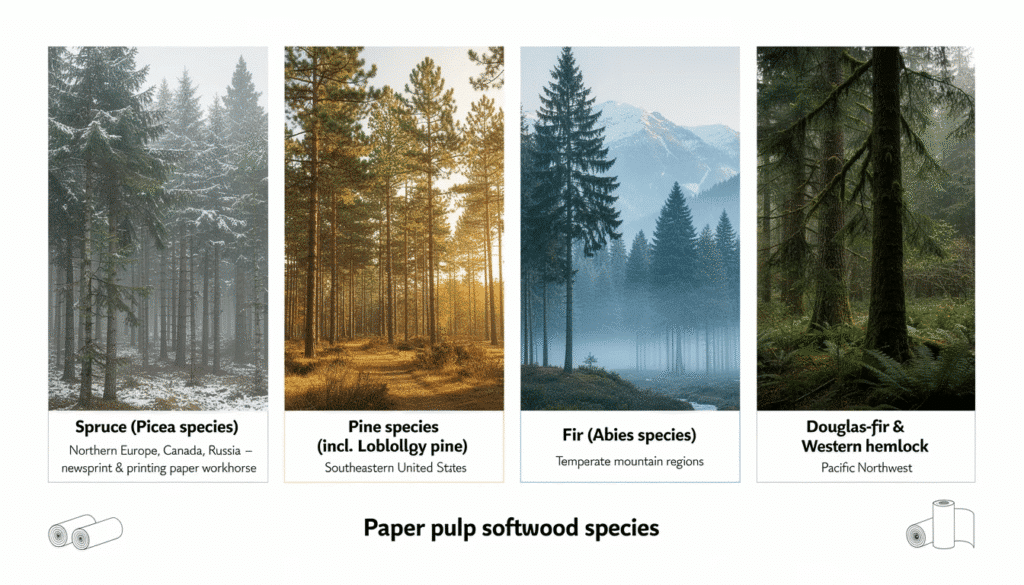

Different types of paper require different fiber characteristics. Here are the most commonly used trees in global paper production:

Softwood (coniferous) pulp trees:

- Spruce (Picea species) in northern Europe, Canada, and Russia—the workhorse of newsprint and printing paper

- Pine species, including loblolly pine in the southeastern United States

- Fir (Abies species) in temperate mountain regions

- Douglas-fir and western hemlock in the Pacific Northwest

Hardwood (deciduous) pulp trees:

- Eucalyptus plantations in Brazil, Portugal, Spain, and parts of Asia—among the fastest-growing pulp sources globally

- Birch in Scandinavia and Russia, valued for smooth writing and printing paper

- Aspen and poplar in North America and Europe

- Acacia plantations in Southeast Asia, especially for tissue paper

Softwood fibers provide the backbone for paper strength, while hardwood fibers fill in gaps for better opacity and a smoother surface. Most paper produced today contains a blend of both, optimized for the final product—whether that’s cardboard, newsprint, or premium drawing papers.

Non-wood plants used to make paper

While wood dominates the global paper supply, many papers are made wholly or partly from other plants. These alternative fibers serve specialty markets, artisanal producers, and regions where wood is scarce or expensive, and different types of paper for craft take advantage of their unique textures and strengths..

Major non-wood fiber plants:

- Bamboo: This fast-growing grass reaches harvestable size in 3-5 years. China, India, and Southeast Asia use bamboo for printing paper and tissue paper. Bamboo contains about 48% cellulose, comparable to many hardwoods.

- Cotton: Cotton linters (short fibers left on seeds after ginning) and recycled cotton rags create rag paper prized for archival quality. Banknotes, fine stationery, and artists’ watercolor papers often contain 100% cotton.

- Hemp: Hemp fibers are exceptionally long and strong. Some specialty and eco-branded papers use hemp, though processing costs limit widespread adoption.

- Flax and linen: Historically important for durable papers, flax fibers still appear in some security papers, artists’ papers, and cigarette papers.

- Sugarcane bagasse: After sugarcane is crushed for juice, the remaining fibre becomes bagasse. Sugar-producing countries in Asia, South America, and Africa use bagasse for packaging, paper cups, and some printing paper. Bagasse contains roughly 40% cellulose.

- Agricultural residues: Wheat straw, rice straw, and kenaf find use in regions with limited wood supplies. Studies suggest agricultural pulps can have half the ecological footprint of forest-based pulp.

These fibers can reduce dependence on trees and turn waste streams into valuable materials. However, challenges include seasonal availability, collection logistics, and the need for specialized processing equipment to handle silica content in straw or gums in bast fibers—considerations that also influence which craft paper supplies for creative projects are most practical to use..

Tree-free and alternative fiber papers

“Tree-free paper” refers to paper made without virgin wood fiber. These products typically use cotton, bamboo, agricultural waste, or recycled fibers as their base.

Common tree-free products:

- Premium cotton stationery and watercolor paper labeled “100% cotton rag” for artists and calligraphers

- Bamboo notebooks and tissue papers marketed as eco-friendly alternatives

- Bagasse-based food containers and paper plates that have increasingly replaced polystyrene in cafés since the 2010s

- Hemp-blend papers sold through specialty stationery retailers

While tree-free papers can reduce forest pressure, they still require water, energy, and sometimes chemicals during production. “Tree-free” doesn’t automatically mean low-impact—the full papermaking process matters, from field to final product.

How plants become paper: from fiber to sheet

Regardless of whether the raw material is spruce logs, bamboo stalks, or cotton rags, the fundamental papermaking process follows the same logic: isolate cellulose fibers, suspend them in water to create pulp, and form that slurry into dried paper sheets.

Pulping methods:

- Mechanical pulping: Wood logs are ground against a rotating stone or refined between metal plates. This method retains most of the lignin (the compound that gives wood its rigidity), producing cheaper pulp suitable for newsprint and paperboard. The tradeoff: mechanical pulp yellows over time and produces weaker paper.

- Chemical pulping: Wood chips are cooked in a cooking liquor—a mixture of chemicals that dissolve lignin and separate cellulose fibers. The kraft process (using sodium hydroxide and sodium sulfide) dominates globally, yielding strong, bright paper pulp. Sulfite pulping offers an alternative for certain specialty papers.

- Non-wood processing: Plants like bamboo, bagasse, and straw require adjusted cooking times and chemical concentrations to remove gums, silica, or other plant-specific compounds before the fibers become usable.

Sheet formation:

- Paper pulp is diluted with water to create a slurry that’s over 95% liquid. This extremely thin layer of fibers suspended in water flows onto a moving screen.

- In traditional handmade papermaking, craftspeople use a mould and deckle to scoop pulp and drain water manually.

- In a modern paper machine, the slurry flows continuously onto a wire mesh belt, where water drains away and fibers begin to interlock.

- Pressing rolls squeeze out additional water as the paper web moves through the machine.

- Heated drying cylinders remove remaining moisture until the paper reaches stable form.

After drying, many papers undergo additional treatments. Sizing agents reduce ink absorption. Coatings add gloss or printability for magazines and brochures. Calendering (passing the sheet between polished rollers) smooths the surface. Throughout these steps, the plant-derived cellulose fibers remain the structural foundation of every sheet.

Environmental considerations of plant-based paper

The choice of which plants supply our paper carries significant environmental implications. From forest management to mill pollution to end-of-life disposal, paper’s plant origins connect directly to sustainability concerns that have shaped the industry for decades.

Key environmental impacts:

- Forest use: Paper and packaging production consumes a substantial share of harvested wood globally. Certification programs like FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) and PEFC promote responsible forestry practices, though not all paper carries these labels.

- Deforestation concerns: Research indicates that about 25% of Germany’s raw paper materials still come from tropical forest sources like Brazil. Without robust certification and recycling, paper production can contribute to habitat loss.

- Waste volumes: Paper and cardboard make up a large fraction of municipal solid waste—estimates range from 25-40% by weight in countries like the United States, depending on the year and measurement method.

- Pollution from processing: Traditional bleaching with elemental chlorine produced toxic dioxins. Since the 1990s, many paper mills have shifted to elemental chlorine-free (ECF) or totally chlorine-free (TCF) bleaching processes.

The role of recycled paper:

- Recycling reuses existing plant fibers, reducing demand for fresh wood. Germany, for example, sources roughly 70% of its paper production from recycled fibers.

- However, fibers shorten and weaken with each recycling cycle. After 5-7 rounds, fibers become too degraded for quality paper.

- Many office papers and packaging products blend virgin and recycled fiber to maintain strength while reducing environmental footprint.

Alternative fibers like bamboo, bagasse, and agricultural residues offer potential benefits by using waste streams or fast-growing plants. At the same time, growing demand for profitable paper crafts—such as paper crafts that sell well—adds another layer of economic incentive to how these fibers are sourced and used. However, their true environmental advantage depends on local farming practices, transportation distances, and processing methods. There are no simple answers—only tradeoffs that informed consumers and policymakers must weigh..

Summary: so, paper is made from which plant?

Today, most paper is made from trees—especially softwood conifers like spruce, pine, and fir for strength, and hardwoods like eucalyptus and birch for smoothness and printability. These species dominate the global paper industry because they offer abundant, scalable, and consistent fiber supplies.

Historically, people created paper and paper-like materials from very different plants. Ancient Egyptians pressed strips of the Cyperus papyrus plant into writing sheets. Early Chinese inventors pioneered true papermaking using paper mulberry bark, hemp waste, and bamboo. For centuries, rag papers made from cotton and linen dominated European production.

Non-wood plants remain important today. Bamboo, cotton, hemp, and sugarcane bagasse serve specialty markets and sustainability-focused brands. Agricultural residues like wheat straw offer promising alternatives with lower ecological footprints than forest-based pulp.

Ultimately, any fibrous plant rich in cellulose can theoretically become paper. What determines actual usage is a combination of economics, processing technology, regional availability, and growing sustainability considerations. Whether you’re holding a newspaper printed this morning, browsing paper crafting inspiration, or using archival cotton stationery, the fibers in your hands trace back to plants—and understanding those origins helps make informed choices about the paper we use every day..