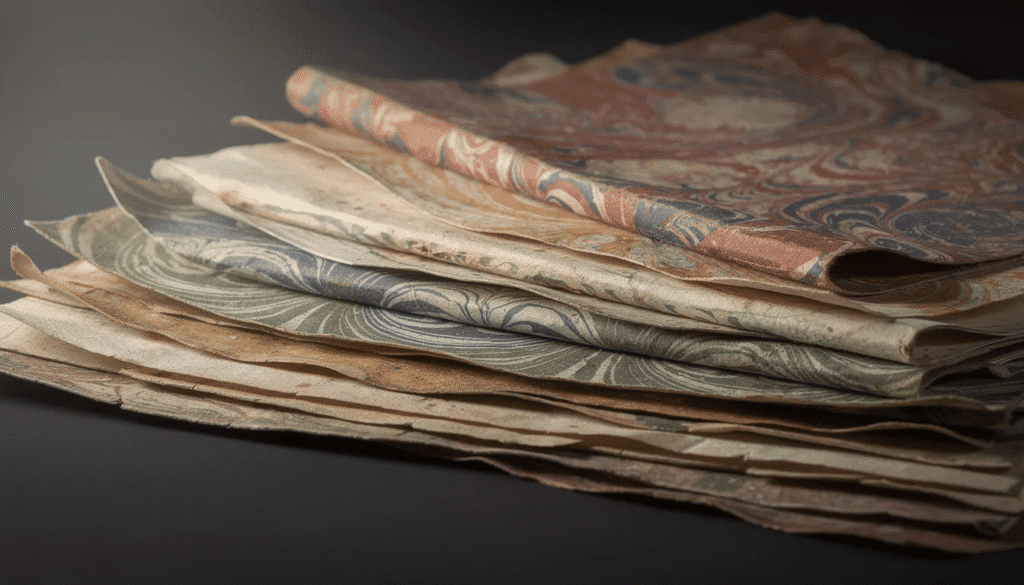

Antique marbled paper represents one of the most captivating decorative arts to survive from the bookbinding workshops of centuries past. Each sheet—whether salvaged from an 18th-century English calf binding or carefully removed from a French ledger dating to c. 1820—carries the fingerprints of its maker in ways that printed reproductions simply cannot match. The swirling colours, the slight irregularities where thrown inks met the viscous bath, and the subtle distortions from hand-laying all mark these papers as genuinely hand crafted objects.

This article is intended for collectors, bookbinders, artists, and anyone interested in the history and craft of decorative papers. Antique marbled paper is valued for its historical significance, unique artistry, and continued influence on book arts and design. Understanding where these papers came from—and how to identify them—opens a window into centuries of craft tradition.

- Origins and Early History of Marbled Paper

- Antique Marbled Paper in European Bookbinding

- Classic Antique Marbled Paper Patterns

- Paste Paper and Other Antique Decorative Papers

- Techniques and Materials Behind Antique Marbled Paper

- Regional Varieties and Exotic Antique Papers

- Collecting, Identifying, and Reusing Antique Marbled Paper

- Antique Marbled Paper in the Contemporary Studio

Origins and Early History of Marbled Paper

The earliest documented marbling tradition emerged in Japan around the 12th century (suminagashi, meaning “floating ink,” is the oldest known form of marbled paper from Japan, dating back to the 10th century). Known as suminagashi, meaning “floating ink,” this technique involved dropping ink onto water and transferring the resulting patterns to paper used for poetry and ceremonial documents. The Hiroba family in Echizen, Fukui Prefecture, claims continuous marbled paper production since 1151 CE—a remarkable 55 generations of craft knowledge shaped by local water conditions particularly suited to the process. Kamakura period examples demonstrate the sophisticated aesthetic sensibilities that Japanese marblers brought to what might seem a simple technique.

A parallel tradition developed in the Near East during the long 16th century. Persian and Ottoman craftsmen created ebru (ebru, meaning “cloud art,” is a Turkish style of marbled paper dating back to the 15th century that uses a thickened liquid made from carrageenan), working in Transoxiana and eventually establishing Istanbul as a major center by the 1500s. Early methods used basic floating techniques, but approximately a century later, marblers like the Safavid-era émigré Muḥammad Ṭāhir developed innovations using finely prepared mineral and organic pigments alongside combs to manipulate floating colours. The result was comparatively elaborate, intricate, and mesmerizing overall designs that defined the craft’s technical foundations.

European merchants—particularly Venetians trading through Mediterranean routes—encountered these papers and began importing them in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. By the 1520s and 1540s, marbled papers appear in German and Italian bindings, suggesting that European craftsmen quickly recognized their potential. For the purposes of this article, “antique” generally refers to hand-marbled papers produced before the early part of the 20th century, when mechanized printing fundamentally transformed production.

As marbled paper traditions spread, their integration into European bookbinding would transform both the craft and the decorative arts—a topic we will explore in the next section.

Antique Marbled Paper in European Bookbinding

Marbled paper’s integration into European bookbinding transformed it from exotic curiosity to workshop staple over roughly two centuries. By the late 16th century, bookbinders in Italy, Spain, and England had adopted marbled endpapers as decorative enhancements for fine bindings (endpapers are the sheets on the inside covers of books, providing a decorative transition between the cover and the text block). In 17th and 18th-century bookbinding, marbled endpapers also served to hide the structural elements of the binding. France particularly embraced the connection between marbling and bookbinding—a relationship that remains strong today—essentially establishing marbled paper’s primary European function as decorative endpapers.

The craft spread broadly across Europe during the 1700s, with marbling common on 18th-century French and Dutch bindings. Peak popularity arrived in the Victorian era during the mid-19th century, when even modest volumes might feature marbled endpapers and edges. This same period, however, saw the beginning of decline as mechanized bookbinding reduced demand for hand-marbled sheets.

Typical uses included:

- Pastedowns and flyleaves in octavo and quarto volumes, protecting the binding structure while adding visual appeal

- Sprinkled or fully marbled page edges on 18th–19th-century Bibles, legal texts, and account books, providing both decoration and a measure of security against page removal

- Cover papers for less expensive bindings where full leather was impractical

Consider a c. 1760 London law book with nonpareil edges—the combed vertical lines protecting the page block while identifying the volume on a shelf of similar bindings. Or examine an 1830s French novel with shell pattern endpapers, the swirling forms complementing the romantic literature within.

Many antique sheets encountered today come from damaged or discarded bindings and ledgers. As books deteriorate, the marbled papers often survive in better condition than the text blocks they once protected, creating a robust market for salvaged sheets.

To better appreciate the artistry and technical evolution of these papers, it is helpful to understand the classic patterns that defined antique marbled paper.

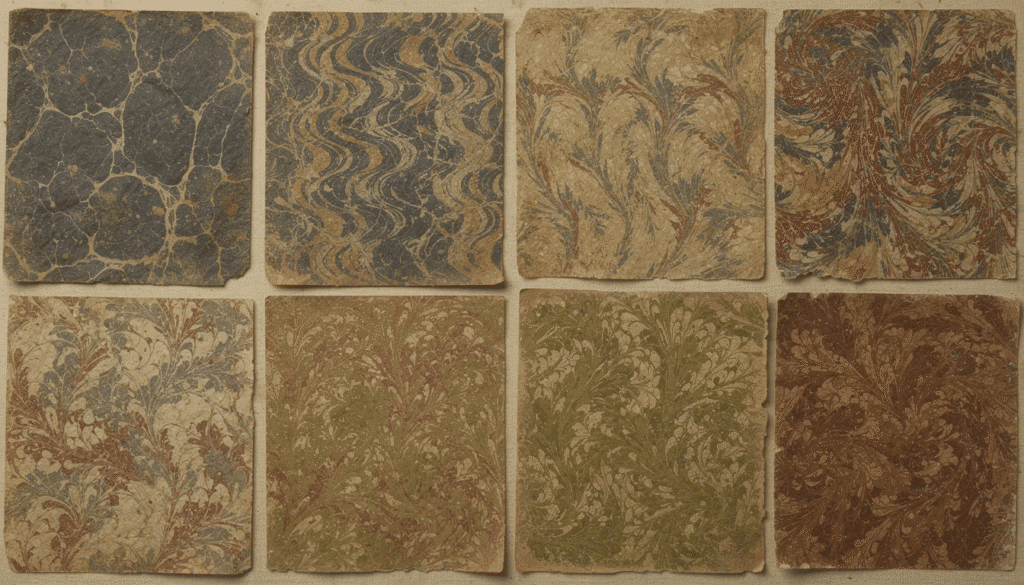

Classic Antique Marbled Paper Patterns

Understanding pattern types helps date sheets and appreciate the technical evolution of the craft. Each major pattern represents a specific manipulation of floating colours, and many variations accumulated across centuries of workshop practice.

The Antique Straight Pattern

The antique straight pattern dates to at least the 17th century and represents one of the most recognizable historical styles. It begins with a feather pattern—colours drawn into elongated, feathery shapes—overlaid with a field of fine white dots thrown across the entire bath. These distinctive white spots, created by dropping dispersant onto the floating colours, give the pattern its characteristic stippled appearance. The antique straight closely resembles natural stone with its combination of flowing veins and scattered speckling.

Turkish and Stone Patterns

The Turkish pattern, one of the earliest Western marbled patterns adopted from Ottoman ebru, involves inks dropped to form rounded spots across the entire surface. The colours spread naturally according to their surface tension and the amount of ox gall or other surfactant mixed with each pigment. Because this pattern creates small grain textures reminiscent of actual stone, it’s sometimes called the turkish base for more elaborate combed designs. The visual effect—random tiny drops in varied drop sizes—requires no combing, making it among the most approachable patterns for beginners while remaining beloved for its organic quality.

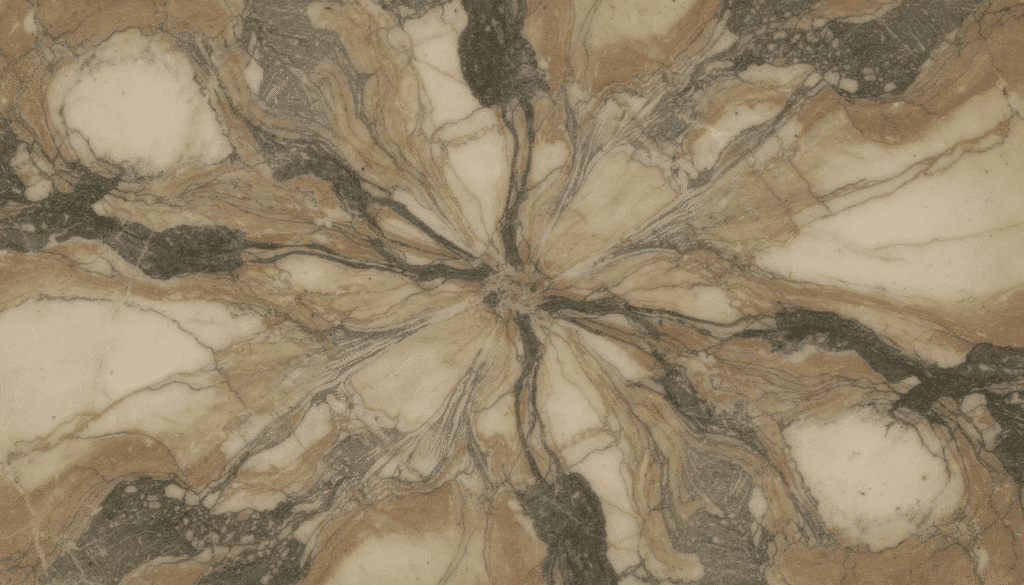

Italian Marble

Italian marble patterns use dispersant drops strategically placed to push colours apart, creating stone-like veining with constricted veins that closely resembles polished natural marbled stone. The tiny veins spread outward from where dispersant contacts the floating colours, and skilled marblers control this expansion to suggest the geological formations found in actual stone quarries. This pattern dominated 18th–19th-century bindings, particularly Italian productions that supplied binders across Europe.

Nonpareil and Combed Variations

Nonpareil—from the French for “without equal”—features closely spaced vertical lines created by drawing a comb through the floating colours. First the colours are laid, then a comb pulled bath vertically, then another comb pulled bath horizontally to create the characteristic fine, regular pattern. The last comb’s teeth set the final spacing. This pattern often serves as a base for more elaborate designs, with variations including:

- Old Dutch pattern: based equally on Turkish spotting and subsequent combing, reflecting Dutch adoption of the technique

- Dutch pattern: similar constructions with regional colour preferences

- Bouquet and Peacock: created using a secondary pass halving the comb spacing, with teeth set at different intervals to create feather or “eye” motifs resembling peacock plumage

Stormont and Storm Effects

The stormont pattern emerged in the 19th century, using dispersants and extra agitation to create cloudy or storm-like effects. In Ottoman marbling, this technique was called “neftli,” made with turpentine. The dark spots distinctive of Stormont patterns—with their characteristic white halos around colour centers—result from fine spots inside larger colour areas being pushed outward. These latter thrown inks create textural complexity impossible to achieve through combing alone.

The Zebra Pattern and Spanish Moiré

The zebra pattern features bold, contrasting stripes created through specific comb movements and colour placement. Meanwhile, spanish moiré uses a wide comb with teeth set at regular intervals, creating undulating wave effects. Both demonstrate how variations in tool design and hand movement produce dramatically different results from the same basic process.

Double Marble Techniques

Double marble involves marbling a sheet, drying it, treating it again with alum, then giving it a second floating pattern. This creates layered visual effects impossible in single-pass marbling. The technique contrasts with the later lithographic process used to mass-produce marble effects—lithographic overprinting could simulate complexity but lacked the depth of genuine double marbling.

Gold Vein and Metallic Effects

Gold vein patterns use bronze inks or metallic pigments to imitate the precious metal veins found in certain decorative stones. Gold vein overprinted onto existing patterns creates particularly luxurious effects. These papers frequently appear on 19th-century deluxe bindings where cost was less constrained.

Pattern identification helps establish rough dating: certain styles predominated in specific eras, and researchers like Richard J. Wolfe have documented these shifts. An experienced eye can often narrow a sheet’s origin to within a half-century based on pattern, colour palette, and paper characteristics alone.

Beyond marbled papers, bookbinders also used other decorative techniques, such as paste paper, which we will explore next.

Paste Paper and Other Antique Decorative Papers

Marbled paper (colour floated on a liquid bath and transferred to paper) differs fundamentally from paste paper, where pigmented paste is applied directly to the sheet and then manipulated. Both appeared together in 18th–19th-century bookbinders’ workshops, and collectors often encounter them mixed in salvage lots.

Printed paste papers involve coating a sheet with coloured paste, then pulling patterns out with combs, fingers, or styluses to reveal the underlying paper. This technique was particularly common on 18th-century German bindings, creating bold geometric or flowing designs depending on the tools used. The same process produces many different spellings in historical sources—paste, pasted, pasted-board—reflecting regional variations in terminology.

“Pulled” paste papers use a different approach: two pasted sheets are pressed together, then peeled apart to create branching vein patterns. The effect can visually resemble marbling’s organic flows, though the underlying technique differs entirely. A pulled paste paper in an 1800 ledger shows sharp, tree-like branching where the paste separated, while Turkish marbling from the same era displays the rounded, floating-ink character of bath-based work.

Combed, daubed, and spatter paste techniques employed simple tools:

- Wooden combs of various tooth spacings

- Rags and sponges for dabbing textures

- Stiff brushes for spattering colour

- Laid or wove paper as the base sheet

Antique marbled paper collections frequently contain paste papers as well. Both filled similar decorative roles in bookbinding, and workshop practices meant the same binder might use either depending on the project, materials available, and desired effect, much as contemporary artisans choose between different handmade paper sheets for creative projects depending on texture, weight, and intended use.

To fully appreciate the artistry of antique marbled paper, it’s important to understand the techniques and materials behind its creation.

Techniques and Materials Behind Antique Marbled Paper

Understanding how antique marbled paper was made helps explain why each sheet is unique and why the craft required such extensive apprenticeship.

Preparing the Size

- Preparing the size: Marblers filled shallow trays with a viscous solution, historically made from carrageenan moss, gum tragacanth, or similar mucilaginous substances. This size had to reach precise consistency—too thin and colours sank, too thick and they wouldn’t spread.

Mixing Colours

- Mixing colours: Pigments or inks were mixed, often with ox gall (bile from cattle gall bladders) or other surfactants to control how each colour would float and interact with others. Dropped sequentially onto the bath, each colour behaved according to its specific formulation.

Dropping and Manipulating Colour

- Dropping and manipulating colour: Using a marbling brush, the artisan would throw colours onto the surface. The ink mixed with air during this throwing process, landing as tiny drops that spread based on surface tension. Then a comb was drawn through the floating colours to create patterns—or multiple combs in sequence, with each pass moving slightly to build complexity.

Transferring the Pattern

- Transferring the pattern: The prepared sheet was laid carefully onto the bath surface, picking up the floating colours. The paper was then lifted, rinsed to remove excess size, and hung to dry. The same process repeated for each subsequent sheet, with the middle part of the bath cleaned between prints.

The Physics of Marbling

Temperature and humidity dramatically affected results. Marblers often speak of the temperamental nature of this process—minute variations in conditions produced entirely different outcomes. Surface tension governed how colours spread, while the size’s viscosity determined how freely patterns could be manipulated. Even dust particles could disrupt the bath.

Specialized Historical Tools

Beyond basic combs, historical marblers used:

- Fine wire mesh for creating dispersant drops that produced “rain” or “storm” textures

- Styluses for drawing feather patterns by dragging through floating colours

- Multiple combs with different tooth spacing for building complex patterns in successive passes

A sheet might require colours dropped, then the bath worked with a wide-toothed comb, followed by a finer comb, and finally stylus work for details—all before the paper touched the surface.

Hand Marbling Versus Printed Imitations

Genuine hand-marbled sheets can be distinguished from lithographic or machine-printed imitations by their irregularities. Hand work produces overlapping droplets, slight registration variations, and the unmistakable character of colours that actually floated. Printed imitations, developed in the 19th century for mass production, lack these qualities despite achieving superficial resemblance.

Creating a single hand-marbled sheet takes approximately 20 minutes for a skilled marbler. Modern machines can produce 1,500 sheets per hour. This productivity difference explains why hand-marbling retreated to specialty markets once mechanization arrived.

With a grasp of the techniques and materials, we can now explore how regional traditions and exotic papers contributed to the diversity of antique marbled paper.

Regional Varieties and Exotic Antique Papers

Different regions adapted marbling techniques to local materials, aesthetic preferences, and available trade goods, creating distinctive regional traditions.

Italian Traditions

Italian marbled paper production—particularly from Florence and Venice—reached considerable sophistication during the 18th and 19th centuries. These papers typically feature relatively light colours on good quality handmade or early machine-made sheets. Patterns like Italian marble and nonpareil were exported widely, supplying binders across Europe. Weight often ranges from 80–100 gsm, with the tactile quality of genuinely hand-formed paper evident in surface texture and chain line patterns.

It nation became synonymous with fine decorated papers, with the Giulio Giannini e Figlio company in Florence representing continuous production across six generations.

French Production

French marbling centers supplied the sophisticated Parisian book trade throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Provincial workshops also produced for local markets. French papers often display refined colour harmonies reflecting contemporary artistic tastes, and many example sheets survive in bindings from this period.

Marbling Beyond Europe

Later but still historical marbled papers emerged from regions including Nepal, India, and Thailand. These used distinctive base papers:

- Lokta (Nepalese paper from Daphne bark)

- Cotton rag papers from Indian mills

- Kozo-based papers from Southeast Asian traditions

These papers create distinctive textures quite different from European productions. However, most available examples date to the 20th century rather than being truly antique—they represent “traditional” methods rather than historical artifacts.

Asian and Middle Eastern antique examples are considerably scarcer in Western markets, as many remain in situ within their originating cultures or have been preserved in institutional collections. European and colonial-era book salvage accounts for most antique marbled sheets currently available to collectors.

With an understanding of regional styles, we can now turn to the practical aspects of collecting, identifying, and reusing antique marbled paper.

Collecting, Identifying, and Reusing Antique Marbled Paper

Building a collection of antique marbled paper requires knowing where to look, how to assess authenticity, and how to handle condition issues responsibly.

Finding Antique Sheets

Typical sources include:

- Broken bindings from the 18th–19th centuries, where the text block has deteriorated but endpapers remain

- Discarded ledgers and account books, often featuring marbled covers or page edges

- Estate clearances where old libraries are dispersed

- Specialist dealers who salvage marbled endpapers and edges from volumes beyond repair

Identification Basics

Distinguishing genuinely hand-marbled antique sheets from later printed imitations requires attention to several factors:

Feature | Hand-Marbled | Printed Imitation |

|---|---|---|

Surface texture | Colours sit on surface with slight dimension | Flat, absorbed into paper |

Pattern irregularities | Overlapping droplets, slight distortions | Mechanical regularity |

Registration | Minor variations between colour layers | Perfect alignment |

Paper type | Often laid paper with visible chain lines | Frequently wove or machine-made |

Check for watermarks, which can help date the paper itself. Compare patterns to established typologies—Turkish, nonpareil, antique straight, Stormont, and other follow recognizable forms. The major differences between authentic and imitation papers become apparent with practice. |

Condition Issues

Antique sheets commonly display:

- Foxing: Brown spots from fungal growth or iron contamination

- Abrasion: Surface wear from handling or binding friction

- Edge losses: Tears or missing corners from removal or deterioration

- Adhesive residues: Previous glue or paste from binding attachment

These condition issues don’t necessarily diminish a sheet’s value for reuse, though they may affect framing or display choices.

Respectful Reuse

Antique marbled papers can find new life through numerous vintage paper craft ideas, including:

- Collage and mixed-media art incorporating surviving strong-pattern areas

- Fine boxmaking using smaller pieces for decorative panels

- New bindings in historically informed styles

- Conservation-minded repairs to damaged books of similar period

- Framed wall pieces highlighting the most visually striking portions

Basic Care Guidelines

Proper storage extends the life of antique sheets:

- Avoid harsh light, which fades pigments

- Control humidity—neither too damp nor overly dry

- Use acid-free folders and avoid contact with acidic materials

- For framing, employ archival matting with UV-protective glazing

With these practical considerations in mind, we can see how antique marbled paper continues to inspire and inform contemporary artists and craftspeople.

Antique Marbled Paper in the Contemporary Studio

Modern marblers and artists increasingly study antique papers to recreate or reinterpret historic patterns. These surviving sheets serve as primary sources for understanding historical colour choices, comb spacing, and layering strategies.

Referencing specific historic styles—reproducing an 18th-century Italian nonpareil or a 19th-century Stormont pattern, for example—connects contemporary practice to centuries of craft tradition. The fine dots, the characteristic veining, the rhythms of combed patterns all carry forward when studied carefully from original examples.

Contemporary artisans typically work on acid-free, pH-neutral papers around 90–120 gsm, ensuring compatibility with conservation practices and archival longevity. This represents an evolution from historical papers, which varied considerably in quality and have often suffered acid deterioration over time.

Antique examples guide:

- Colour choices: Historical palettes differed from modern preferences

- Comb spacing and tooth configuration: Recreating specific patterns requires matching historical tools

- Layering strategies: Understanding how colours were dropped sequentially, moving slightly between drops, to build depth

Antique marbled paper thus serves dual roles: as a collectible remnant of book history worthy of preservation, and as a living source of technical and aesthetic inspiration for new hand-marbled sheets. The tiny stones of pigment visible in some historical papers, the evidence of specific techniques in others—all offer lessons for those willing to look closely and learn from the marblers who came before.

Whether you’re examining a salvaged sheet from a broken binding, studying patterns to inform your own marbling bath, or simply appreciating the artistry of papers created centuries ago, antique marbled paper rewards attention. These sheets connect us to workshops where craftsmen guarded their secrets, to bookbinders who chose specific patterns for specific volumes, and to the readers who handled these books across generations. Start looking—in antiquarian bookshops, estate sales, or your own family’s old volumes—and you’ll find these papers waiting to share their stories.